When a shotgun fires multiple pellets, they spread out in a cloud of pellets upon leaving the barrel. This is known as the shotgun pattern or shotgun shot spread. We've already studied how to determine the shotgun pattern earlier and the reader is advised to refresh their memory from the earlier article.

Now the key is that the largest number of pellets must penetrate in a 30 inch diameter circle, such that if a bird silhouette was to be placed on the circle, that the silhouette cannot be placed anywhere where at least 3 pellets are not going through it.

In order to increase the number of pellets within the 30 inch circle, a choke is often employed. Chokes may be built into the barrel, as part of the manufacturing process, or the end of the barrel may be threaded and the user can screw on a removable choke to the end of the muzzle as needed. This way, the user may be able to use different chokes depending on the number and diameter of the pellets used.

Since removable chokes are more modern, we will now study the history of choked barrels (i.e.) barrels manufactured with a built in choke.

The basic principles of choke-boring seem to have been invented by Spaniards, as we find the first mention of improving shooting patterns by various boring methods in Spanish books. M. de Marolles in his book, La Chasse au Fusil, states that some gunmakers in his time maintained that, in order to throw shot more closely, the barrel diameter should be narrower in the middle than on the breech or the muzzle end; while others insisted that the barrel must gradually contract from breech to muzzle. He goes on to describe methods to achieve these results, as were in vogue during his time. J.W. Long, an American author, in his book, American Wild Fowl Shooting, claims that choke-boring was an American invention and attributes the discovery to one Jeremiah Smith of Smithfield, Rhode Island, who was making choke-bored barrels, as early as 1827. The first known patent was granted to an American gunsmith, one Mr. Roper, on April 10th 1866, who preceded another claimant, an English gunmaker, Mr. Pape, by just six weeks.

While these early inventions were by American gunsmiths, they had not fully understood choke boring and therefore, a lot of their guns would lead, shoot irregular patterns and not shoot straight. It was left to an English manufacturer, W.W. Greener, to invent a method of choke boring that became the most widely used method in the later part of the 19th century. It was because of the popularity of the Greener method of boring that some authorities falsely give W.W. Greener the credit for inventing choke boring, though he himself never claimed to invent it.

W.W. Greener was a well-known gunmaker in Birmingham in the 19th century (the firm is still around today). His first intimation of a choke formation was from a customer's letter in early 1874. This customer had ordered a custom gun and in his special instructions to Greener, he described a choked barrel, though he did not specify its size or shape, or how it was to be obtained. However, W.W. Greener was intrigued enough to conduct many experiments to determine how to make the best profile and size of the choke for any given bore diameter. He also invented new tooling to make this boring possible. After many months of experimenting, he figured out how to make appropriate choke profiles for any bore of shotgun.

The Greener choke consists of leaving the barrel mostly cylindrical, but creating a constriction in the barrel towards the muzzle end of the barrel, as can be seen in the figure above. Before this method was invented, most people would either make the breech end of the barrel of a slightly larger diameter for up to 10 inches of barrel length from the breech, or they would bore the middle of the barrel to a smaller diameter and make the breech and muzzle of a larger diameter, or they would simply leave the barrel as a true cylinder (no choke).

On December 5th 1874, Mr. J.H. Walsh, the Editor of Field magazine, mentioned the Greener choke in an article, that read:

"We have not ourselves tested these guns, but Mr. W.W. Greener is now prepared to execute orders for 12-bores warranted to average 210 pellets of No. 6 shot in a 30-in. circle, with three drachms of powder, the weight of the gun being 7.25 lb. With larger bores and heavier charges, he states that an average pattern of 240 will be gained. As we have always found Mr. W.W, Greener's statements of what his guns would do borne out by our experience, we are fully prepared to accept those now made".

The article created a sensation because the very best 12-bore shotgun in the London public gun trial of 1866 could only generate an average pattern of 127. The very next issue of Field magazine contained an ad from W.W. Greener guaranteeing a pattern of 210 on his 12-bore guns. There was also a letter to the Editor in the next issue, from a reader of the magazine, confirming that his latest purchase from W.W. Greener did indeed meet this claim and more. Naturally, such statements created a huge controversy among gun manufacturers and readers, and the Editor of Field magazine was compelled to send a Special Commissioner to witness and verify the shooting of Greener guns. The Special Commissioner not only verified the claims, he actually got an average pattern close to 220 during his testing! After that, several other manufacturers claimed to be in possession of the same method of boring as W.W. Greener and therefore, the proprietors of Field magazine decided to conduct a public trial, the London Gun Trial of 1875, to verify various manufacturer claims. Greener-made choke bores won overwhelmingly in this trial, as well as the London trials of 1877 and 1879 and the Chicago trials of 1879 and led to the fame of his company spreading.

The Greener method of choke-boring was later adopted by other manufacturers and became the dominant form of choke boring. Modern chokes today are usually screwed on to the muzzle end of the barrel and slightly change the diameter of the muzzle in much the same way.

Showing posts with label Shotgun pattern. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Shotgun pattern. Show all posts

Tuesday, February 22, 2011

Sunday, February 20, 2011

Shotguns: Ammunition

Shotguns are designed to fire a wide variety of ammunition, generally more than other firearm types. We will look at the various types of ammunition in this post.

Before we start, the reader is advised to revisit an earlier article on bore/gauge of a shotgun, which will come in useful to understand some concepts discussed in this article. The reader may also find it useful to peruse the article on shotgun pattern testing.

The first, and most common type, is the shotshell. This is a cartridge that contains a number of pellets, usually made of lead, steel alloy, bismuth alloy or titanium composite. The most common type of shotshell is birdshot, which is commonly used to hunt birds. It consists of a cartridge containing dozens to hundreds of small pellets or ball-bearnings.

The shotgun shell is cylindrically shaped. In earlier days, the outer case was made of brass or thick paper. Modern shotgun shells are usually made of plastic with a thin hollow brass base cover, such as the illustration above. From left to right, we have the brass base of the cartridge, the propellant material (the gray part) which sits inside the brass base and extends out of it, a lot of wadding (the olive, pink and brown bands), the shot pellets and finally, another wad (the brown band on the right) that holds the shot pellets in the cartridge. The purpose of the olive, pink and brown wad is two-fold. First, it provides a gas seal between the pellets and the propellant. If it is not there, the propellant gas will simply flow through the gaps between the pellets instead of propelling the pellets. The second reason is that the wadding acts as a shock absorber or a cushion. When the shell is fired, the wadding gets crushed first and absorbs some of the shock. Without it, many pellets could get deformed by the propulsive force and thereby fly in the air erratically. The cushioning provided by the wadding prevents this.

The pellets in a shotgun shell are of uniform size. In earlier days, the pellets were mostly made of lead, using a process we described previously, because lead is cheap, easily formed and widely available. However, lead is a poisonous substance and can cause lead poisoning (e.g.) pellets that fall into ponds when hunters are hunting water birds. Water fowl could accidentally ingest some of these pellets and end up poisoned. Then, these could be eaten by birds of prey or animals and in turn, they get poisoned as well. People drinking the water could get affected too. These days, the environmental effects of lead are being taken more seriously and therefore, lead pellets are banned in several areas. Hence, modern pellets are now made of steel, bismuth or titanium composites.

Birdshot, like the name suggests, is used to hunt birds. Different gauges are used depending on the species of birds being hunted.

The next variation of shotgun shells use buckshot. These are similar to birdshot, except that the pellets are larger in diameter. Buckshot is designed to take down larger game animals, such as deer (which is why it got the name "buck" shot).

The next common variant is the solid slug. This is a single, solid, heavy bullet used to hunt large game. Many slugs already have rifling cut into them. The first design of a solid slug was from a German designer called Wilhelm Brenneke in 1898. His design has remained largely unchanged until now.

The above image is of a Brenneke type slug. Notice the grooves cut into the sides of the slug. As before, there's a large amount of wadding (the white and brown parts) between the propellant and the slug. This kind is very popular in Europe and sometimes referred to as "European type" slug.

Another design is the Foster slug, designed by an American named Karl Foster in 1931. In this type of slug, there is a deep hollow inside, so that the center of mass is closer to the tip of the slug. This is designed for smoothbore barrels and because of the position of the center of mass, it doesn't tumble in the air because the drag causes the back of the slug to stay behind the front (much like a shuttlecock's feathers). This type is popular in the US and is sometimes referred to as the "American slug". It is also possible to fire this type of slug through a rifled barrel, but it causes lead buildup in the rifling grooves to happen at a faster rate.

Yet another type is the sabot slug. The word "sabot" comes from French, where it was used to describe a type of shoe worn by many workers during the industrial age. Incidentally, there was a period where the French workers went on strike, protesting their work conditions, and threw their sabot shoes into the industrial machines, hoping to jam them up. This is the origin of the word "sabotage"! In a sabot slug, the slug is usually an aerodynamic shape that is smaller than the barrel, surrounded by an outer shoe (the sabot) that provides a tight gas seal. The sabot gets deformed by the propellant pressures, while the slug inside is largely undeformed and intact. In case of rifled barrels, the sabot also has the rifling and therefore provides spin to the bullet. Once the bullet clears the barrel, the sabot separates from the bullet and falls down and the undeformed bullet continues on its way. This provides for better accuracy and faster velocity of the bullet. On the flip side, sabot slugs are more expensive and more time-consuming to manufacture.

The next type of shotgun ammunition is the bean bag round, also known by its trademark, flexible baton round. It consists of a small fabric container filled with birdshot. It is designed to be "less lethal" than the rounds we've studied so far. This type of round is designed to stun a person rather than kill them. Of course, fired at close range, it can be lethal as well. In longer ranges, it could be lethal if it strikes a vulnerable part of a person's anatomy, such as the throat or solar plexus. This type is typically used by police to incapacitate and capture a suspect. Other variations use rubber shot instead of bean bags for the same effect.

Another older form of the bean bag round was the rock salt shell. As the name suggests, shells were filled with rock salt crystals. Since salt crystals are brittle, these shells were not as lethal at longer ranges, but still caused a stinging bruise, enough to dissuade a person from attacking. These were used by police and rural farmers in earlier days.

Another type of shotgun shell is used for riot control. This is the gas shell and it normally contains pepper gas or tear gas.

Before we start, the reader is advised to revisit an earlier article on bore/gauge of a shotgun, which will come in useful to understand some concepts discussed in this article. The reader may also find it useful to peruse the article on shotgun pattern testing.

The first, and most common type, is the shotshell. This is a cartridge that contains a number of pellets, usually made of lead, steel alloy, bismuth alloy or titanium composite. The most common type of shotshell is birdshot, which is commonly used to hunt birds. It consists of a cartridge containing dozens to hundreds of small pellets or ball-bearnings.

Public domain image

The shotgun shell is cylindrically shaped. In earlier days, the outer case was made of brass or thick paper. Modern shotgun shells are usually made of plastic with a thin hollow brass base cover, such as the illustration above. From left to right, we have the brass base of the cartridge, the propellant material (the gray part) which sits inside the brass base and extends out of it, a lot of wadding (the olive, pink and brown bands), the shot pellets and finally, another wad (the brown band on the right) that holds the shot pellets in the cartridge. The purpose of the olive, pink and brown wad is two-fold. First, it provides a gas seal between the pellets and the propellant. If it is not there, the propellant gas will simply flow through the gaps between the pellets instead of propelling the pellets. The second reason is that the wadding acts as a shock absorber or a cushion. When the shell is fired, the wadding gets crushed first and absorbs some of the shock. Without it, many pellets could get deformed by the propulsive force and thereby fly in the air erratically. The cushioning provided by the wadding prevents this.

The pellets in a shotgun shell are of uniform size. In earlier days, the pellets were mostly made of lead, using a process we described previously, because lead is cheap, easily formed and widely available. However, lead is a poisonous substance and can cause lead poisoning (e.g.) pellets that fall into ponds when hunters are hunting water birds. Water fowl could accidentally ingest some of these pellets and end up poisoned. Then, these could be eaten by birds of prey or animals and in turn, they get poisoned as well. People drinking the water could get affected too. These days, the environmental effects of lead are being taken more seriously and therefore, lead pellets are banned in several areas. Hence, modern pellets are now made of steel, bismuth or titanium composites.

Birdshot, like the name suggests, is used to hunt birds. Different gauges are used depending on the species of birds being hunted.

The next variation of shotgun shells use buckshot. These are similar to birdshot, except that the pellets are larger in diameter. Buckshot is designed to take down larger game animals, such as deer (which is why it got the name "buck" shot).

The next common variant is the solid slug. This is a single, solid, heavy bullet used to hunt large game. Many slugs already have rifling cut into them. The first design of a solid slug was from a German designer called Wilhelm Brenneke in 1898. His design has remained largely unchanged until now.

A Brenneke slug. Public domain image

The above image is of a Brenneke type slug. Notice the grooves cut into the sides of the slug. As before, there's a large amount of wadding (the white and brown parts) between the propellant and the slug. This kind is very popular in Europe and sometimes referred to as "European type" slug.

Another design is the Foster slug, designed by an American named Karl Foster in 1931. In this type of slug, there is a deep hollow inside, so that the center of mass is closer to the tip of the slug. This is designed for smoothbore barrels and because of the position of the center of mass, it doesn't tumble in the air because the drag causes the back of the slug to stay behind the front (much like a shuttlecock's feathers). This type is popular in the US and is sometimes referred to as the "American slug". It is also possible to fire this type of slug through a rifled barrel, but it causes lead buildup in the rifling grooves to happen at a faster rate.

Yet another type is the sabot slug. The word "sabot" comes from French, where it was used to describe a type of shoe worn by many workers during the industrial age. Incidentally, there was a period where the French workers went on strike, protesting their work conditions, and threw their sabot shoes into the industrial machines, hoping to jam them up. This is the origin of the word "sabotage"! In a sabot slug, the slug is usually an aerodynamic shape that is smaller than the barrel, surrounded by an outer shoe (the sabot) that provides a tight gas seal. The sabot gets deformed by the propellant pressures, while the slug inside is largely undeformed and intact. In case of rifled barrels, the sabot also has the rifling and therefore provides spin to the bullet. Once the bullet clears the barrel, the sabot separates from the bullet and falls down and the undeformed bullet continues on its way. This provides for better accuracy and faster velocity of the bullet. On the flip side, sabot slugs are more expensive and more time-consuming to manufacture.

The next type of shotgun ammunition is the bean bag round, also known by its trademark, flexible baton round. It consists of a small fabric container filled with birdshot. It is designed to be "less lethal" than the rounds we've studied so far. This type of round is designed to stun a person rather than kill them. Of course, fired at close range, it can be lethal as well. In longer ranges, it could be lethal if it strikes a vulnerable part of a person's anatomy, such as the throat or solar plexus. This type is typically used by police to incapacitate and capture a suspect. Other variations use rubber shot instead of bean bags for the same effect.

Another older form of the bean bag round was the rock salt shell. As the name suggests, shells were filled with rock salt crystals. Since salt crystals are brittle, these shells were not as lethal at longer ranges, but still caused a stinging bruise, enough to dissuade a person from attacking. These were used by police and rural farmers in earlier days.

Another type of shotgun shell is used for riot control. This is the gas shell and it normally contains pepper gas or tear gas.

Breaching rounds are often seen in use with police and military units. This is a special round designed to destroy door locks and door hinges, without endangering nearby bystanders. These rounds are also called Disintegrator or Hatton rounds. The slug is made of a dense metal powder, which is held together by a binder material such as wax. When fired at a door lock from close ranges, the slug destroys the lock and quickly disintegrates into a metal powder, instead of ricocheting somewhere or penetrating through the door. This is what makes is suitable to be used in tight confined spaces.

There are also other ammunition types, such as those that provide a lot of flash, or a whistling noise. These are used to scare or disorient animals, but are not lethal.

As you can see, there are many types of ammunition for shotguns, all for different uses.

Monday, January 17, 2011

Testing Firearms: Shotgun Pattern Test

People who use shotguns for hunting birds often use ammunition that contain multiple pellets or ball bearings. When such a cartridge is shot, the pellets spread out about a certain area, depending on the distance to the target. The pellets leave the shotgun in approximately the same order that they were in the cartridge and continue in a compact mass, until they hit a target, or fall on the ground. In order to reduce the area of concentration of the pellets, people employ various devices on the barrel such as a cylinder choke, skeet choke, modified choke, full choke etc. Of course, different choke types work differently with different ammunition types and hence testing is needed to determine the most effective combinations.

The standard way to test the shotgun pattern is to take a square sheet of paper around 40-45 inches long on each side. The tester mounts this sheet of paper at a distance of 40 yards. The tester then loads the shotgun with a cartridge that has a known number of pellets and shoots at the target. After this, the shooter looks at the paper and draws a circle of 30 inches diameter around the area with the greatest concentration of pellets.

Then the tester counts the number of holes inside this 30 inch circle. Say there are 150 holes inside the circle and the tester knows that the cartridge had 200 pellets loaded. Therefore the tester can say that this shotgun shoots with a 75% pattern for this choke and cartridge load combination.

The tester repeats this test five or more times with a given cartridge load and computes the average to get the shotgun pattern. Obviously, the type of choke used, the number and size of the pellets in the cartridge and the material of the pellets all may have an effect on the pattern density, so the tester tries the same test out with different combinations to find out which of these produce the best patterns.

In order to keep the tests accurate, one needs to make sure that the cartridges used in this test have the same number of pellets or ball bearings each time. One way to do this is to weigh the pellets before loading them into the cartridge. The following table illustrates the average number of pellets per ounce of different standard pellet sizes for both lead and steel pellets:

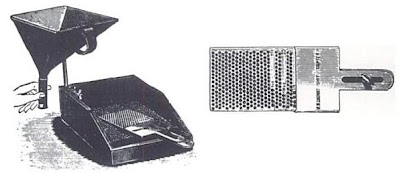

Of course, this assumes that the pellets are all of the same shot size. Some people don't believe in weighing the pellets to get a count. Instead, what they do is use a simple counting device, such as the one shown below:

It consists of a flat trowel made of brass or steel, with a number of holes drilled into it. There is a sliding cover on the handle that can be used to vary the number of holes exposed on the face of the trowel. The tester pushes the trowel into a pile of pellets or bearings and slowly withdraws it. Pellets will stick to the holes and those that are not in any holes can easily be separated. Any misshapen or undersized pellets are also easily visible, so they can be removed as well. The tester can thus easily load the exact same number of pellets into multiple cartridges.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)