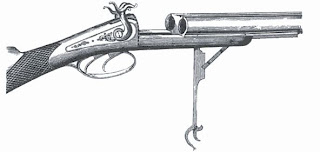

In the case of combination guns, cape guns and paradox guns that we studied earlier, these are all double-barreled firearms. A drilling gun, on the other hand, has three barrels. Generally, two of these barrels are smooth and designed to be used with shotgun cartridges and the third barrel is rifled. However, some other combinations are possible as well, as we will see below soon.

The word "drilling" is actually a corruption of the German word "dreiling", which means "triplet" ("drei" means "three" in German). Several of the early guns of this class were made in German-speaking areas of Europe, for hunting purposes.

The reasons for developing a firearm like this were the same as for all the other firearms we have studied in the previous four posts (viz.) the hunter doesn't need to carry a separate shotgun and rifle, the hunter can be prepared for a wide variety of game, poorer hunters can purchase one weapon that can be used both as a rifle and a shotgun, instead of purchasing a separate rifle and a shotgun etc.

The most common variety of drilling gun has three barrels arranged in an inverted-triangle manner, with the upper two barrels being shotgun barrels of identical bore and the bottom barrel is rifled.

Another fairly common variant has the barrels arranged as a triangle, where the bottom two barrels are shotgun barrels and the top barrel is rifled. In this configuration, the rifled barrel is generally pretty small caliber (something like .22 Long Rifle or .22 Hornet). This variant is called "Schienendrilling" in German.

A rarer variant is a gun that has two rifled barrels and one shotgun barrel. These are harder to construct because the rifle barrels must be carefully aligned during manufacturing, so that they shoot at the same point of aim at some given distance. This is the same process that is done to double-barreled shotguns as well, but shotguns have much short ranges and wider shot patterns, so a small misalignment are not so obvious with shotgun barrels. Due to the precision manufacturing processes required to make the rifled barrels, these firearms usually cost about twice as much as common-drilling firearms.

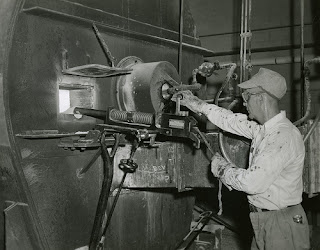

In the above image, we have a drilling gun where the top two barrels are rifled and the bottom barrel is a shotgun barrel. This arrangement is called "Dopplebuchs dreiling" in German (which means "double rifle drilling"). Note that the two rifled barrels in the above image are the same caliber. Some of the guns of this type can fit large rifle cartridges, such as .375 Magnum, .470 Nitro Express etc. and can be used to hunt dangerous game such as lions and elephants.

However, this is not the only possible arrangement, as some hunters prefer two different rifle calibers in their guns. In this case, the shotgun and one rifled barrel are placed in an over and under arrangement and a smaller-caliber rifle barrel is placed on one side:

Another very less common variant has two shotgun barrels of the same caliber in an over-and-under arrangement, with a rifled barrel on one side.

There is also a drilling arrangement where all three barrels are all arranged vertically. In this variant, the top barrel is a shotgun and the bottom two barrels are rifles of different calibers.

The above image shows an example of this type. This is a very rare configuration that is seldom encountered.

There are also variants that have three shotgun or three rifled barrels, but we won't talk about those here because they are not designed to be used as shotguns and rifles simultaneously.

Finally, we have a variant called "Vierling" in German, which is a four barreled weapon. The name comes from "Vier", the German word for "four". Firearms of this type have four barrels in a diamond shaped configuration:

Vierling barrels

Drilling guns were usually made by smaller manufacturers and each maker generally picks whichever barrel configurations they like. Some of them will adjust the barrel configurations based on customer requirements. Many of the well known manufacturers of this class of firearms are German, and they were mostly originally located around the city of Suhl in Germany before World War II. After World War II, the city of Suhl went to East Germany and some of these companies were forced to move to other cities in West Germany and others were forced to close their doors. A large number of drilling hunting rifles were also confiscated and destroyed by Allied forces after World War II, as part of disarming the German population. Hence, some types of drilling guns are very rare now and command a high price among collectors. Some of the well-known manufacturers are Krieghoff, J.P. Sauer & Sohn, Eduard Kettner, Christoph Funk, Heym etc. and all of these, except for Christoph Funk, are still in business currently and manufacturing fine quality drilling guns even today.